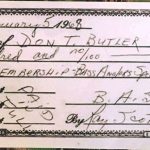

Don Butler

Don Butler (1930 – 2004)— He’s been called Ray Scott’s “guardian angel” and the “patron saint of bass fishing.” While Don Butler might not have agreed with those descriptions, there’s no doubt Butler came to the rescue at several junctures in the birth and growth of Scott’s Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (B.A.S.S.).

When Scott was organizing his first professional bass tournament, the All American at Beaver Lake, Arkansas, in 1967, Butler convinced enough of his fellow Tulsa Bass Club members to put up $100 entry fees and help make the event a success.

In January 1968, as he was forming B.A.S.S., Scott met with the Tulsa Club — one of the first bass fishing clubs in America — to get its support. The meeting was getting unruly as Scott presented his idea to start an organized society for bass fishermen. Some were skeptical of Scott’s ability to make bass fishing a professional sport like golf. Finally, Butler, who helped found the club, stood up and restored order. “Everybody shut up and let this man tell us what he wants to do,” he said.

By the end of the evening, the Tulsa Bass Club bought into that idea. Butler, a lumberyard owner whose store also sold fishing tackle, soon became the first member of B.A.S.S.

“I did it more to encourage him than to have the elite status of being the first to join,” Butler explained later. “I thought that if I could fire Ray up, then it would inspire him to get the idea going. And I wanted to be part of it. I didn’t know where it was going, and neither did Ray, but I believed in him and his idea to bring us all together.”

Months later, Scott was struggling to push B.A.S.S. over the top and send it on its rollercoaster ride to growth and success. The two talked over the phone on a frequent basis, and during one call Scott told Butler about a warranty card list he needed to buy from Abu Garcia for a direct mail campaign. Valued at $10,000, the list was much too pricey at the time for Scott. The next morning, he received an anonymous Western Union Telegram directing him to go to a local bank. There, he was shocked to collect $10,000 from an unknown donor, which later proved to be Butler.

In addition to being a visionary, Butler was a topnotch angler and an entrepreneur. Back when spinnerbaits were just beginning to catch on, Butler designed and introduced the “S.O.B.,” which stood for Small Okiebug Spinnerbait. That bait earned Butler the title of world champion when he won the second Bassmaster Classic, held in 1972 on Percy Priest Reservoir at Nashville, Tennessee.

Butler earned another B.A.S.S. national tournament title, winning the 1973 Arkansas Invitational, on Beaver Lake, with an incredible catch of 56 pounds, 14 ounces. He fished a total of 26 tournaments before health issues forced him to retire. But during his brief career, Butler finished in the Top 10 in half of the events he fished, and he almost always ended in the Top 30.

Recognizing business opportunities in the fishing industry, Butler founded a wholesale tackle business he called Okiebug Distributing Co. One of his early customers was an up-and-coming pro angler on the B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail who was getting into the retail business. The young man, Johnny Morris, would fill up a U-Haul trailer with bass baits and tackle from Butler’s warehouse and haul it back to Springfield, Missouri, to stock his Bass Pro Shops store.

When Scott introduced catch-and-release to bass fishing and mandated that tournament contestants keep their catch alive, it was Butler who designed the first aerated livewell.

A dedicated conservationist, Butler also donated his time and resources to programs designed to introduce youngsters to fishing and other outdoor sports.

Reflecting on his support and encouragement of Ray Scott and his grand scheme of organizing bass anglers, Butler recalled, “It was hard to believe what he said back then. Some people were cynical, and others believed in it like I did. Now, to see it really happen has been a great, fulfilling reward to me.”

Butler died in December 2004 after a long battle with cancer. He was 74 years old.

Don Butler

Jerry McKinnis (1937 – 2019) Jerry McKinnis comes to us as one of the elite few who will ever be inducted into the Hall of Fame, who did not make his living as a full-time tournament fisherman. Instead, he made it through almost forty years of providing outstanding television programming to millions of viewers around the world. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, and still a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals, he came into fishing rather naturally when he moved to the state of Arkansas at an early age.

He began his fishing and business career on the famous White River where he was one of the more popular fishing guides to be found. As his business knowledge moved forward, so did he. After moving to Little Rock, Jerry found that his fishing prowess provided him ample opportunities to “get in front of the camera” when he started giving fishing reports from area lakes. Wanting to provide as much coverage to fishing as possible, he purchased a film camera so that he could show his audience his weekly catches. From the mid 60’s until 1979, his man’s weekly fishing program, “The Fishin’ Hole” was seen around America, in spot markets. In 1979 he and his business partner Jim Manion took “The Fishin’ Hole” to a national audience, when they signed on with a relatively new sports broadcasting network called, “ESPN”. In march 2000, “The Fishin’ Hole” celebrated it’s 36th season on the air and its 20th year as being the anchor of ESPN’s outdoors block. “The Fishin’ Hole” is the second longest running program on ESPN, behind the wildly popular “Sport Center”.

ESPN’s programming director, Gary Morgenstern, has even said that this man’s production company, JM Associates, “is this network’s best friend.” In addition, JM Associates produces a number of different fishing and outdoor programs for ESPN, inc;uding: “The Spanish Fly”; “The Guides” with Bobby and Billy Murray; “The Bass Class” with Denny Brauer; the Citgo BassMaster Tournament Trail and Rick Ruoff’s “Orvis Sporting Life”. JM Associates also produced the Iditarod sled dog race; the Wal*Mart FLW Tour; ESPN’s Stihl Timbersports series; the U.S. Open Racquetball Championship; Great American Events; and countless other specials. In the late 60’s, when fellow Hall of Fame member Ray Scott was getting his Bass Anglers Sportsman Society off the ground, Jerry found time to compete, and succeed, with the early day heroes of bass fishing. While the prize money wasn’t what it is today, our inductee did take home checks in two/thirds of the tournaments he competed in.

Jerry McKinnis

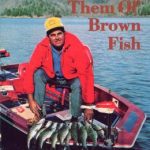

Billy Westmorland (1937 – 2002) — No angler is more synonymous with smallmouth bass fishing than Billy Westmorland. Born in Clay County, Tennessee, in 1937, Westmorland grew up a short cast from Dale Hollow Reservoir, a deep, clear TVA impoundment straddling the Tennessee and Kentucky borders that held giant smallmouth.

While a schoolboy, he would hang around docks on the lake chatting with the local guides and picking their brains about smallmouth fishing. Many of these old timers had hunted rabbit and quail in the hills and “hollers” that were flooded following the dam’s construction; they knew every inch of what lay beneath the lake’s surface and often shared their knowledge with the eager youngster. Westmorland occasionally skipped school to go fishing, and he became obsessed with catching smallmouth as big as the ones the guides would bring back to the docks. By the time he was 13 years old, Westmorland knew the 27,700-acre reservoir well enough to start guiding from a rental rowboat. At first he’d have to wait around the dock until all the other guides had been booked before getting a client, but word eventually spread throughout the lake that “the kid” knew what he was doing and Westmorland began getting regular bookings, often from repeat customers.

While most of Dale Hollow’s veteran guides trolled big diving plugs or fished live bait on heavy tackle for smallmouth, Westmorland gained a reputation for catching giant bronzebacks on light spinning tackle, routinely using 4- and 6-pound line and small lures like the “fly and rind” (a tiny hair jig with a pork rind trailer); this was before the term “finesse fishing” had even been coined. Through his insatiable curiosity about smallmouth, Westmorland learned the depth ranges, bottom compositions and types of structure most likely to hold the biggest fish. He also discovered that trophy-class smallmouth often become most aggressive on the roughest, nastiest winter days.

Westmorland may be the only bass angler to have ever caught both a 10-pound largemouth and a 10-pound smallmouth (his biggest bronzeback weighed 10 pounds, 1 ounce on certified scales). In his classic memoir on smallmouth fishing, “Them Ol’ Brown Fish,” Westmorland told of hooking and losing a behemoth smallmouth one blustery Christmas day on Dale Hollow that he felt sure would have beaten the world record (11 pounds, 15 ounces – also from Dale Hollow). Outdoor writers spread the word about Westmorland’s smallmouth-catching prowess through newspaper and magazine articles. As his reputation grew, he began designing and endorsing lures and tackle geared specifically to smallmouth, a segment of the bass fishing market that had previously been virtually ignored.

In the early 1970s, Westmorland joined Ray Scott’s fledgling B.A.S.S. Tournament Trail and proved to be expert at catching big largemouth as well as big smallmouth. He competed in B.A.S.S. tournaments for seven years, qualifying for the Bassmaster Classic six times and winning three Tournament Trail events.

In the 1980s he became one of the first professional anglers with his own television show, “Billy Westmorland’s Fishing Diary.” Long before the advent of email, Westmorland would spend hours personally responding to fishing fans across North America who wrote him asking for his smallmouth fishing insights. Although his birth name was spelled “Westmoreland,” he claimed to have dropped the second “e” because it allowed him to sign autographs more quickly.

Westmorland died in 2002 at age 65 and is the first angler to be inducted into the Bass Fishing Hall of Fame posthumously. The stretch of highway between Celina, Tennessee, and Horse Creek Resort (the Dale Hollow dock that Westmorland frequented) has been officially designated as the Billy Westmorland Memorial Highway by the State of Tennessee.

Billy Westmorland

Harold Sharp (1927 – 2015) — A career in the railway industry teaches a person the importance order, organization, punctuality and consistency. After 26 years of living and working by those watchwords, Harold Sharp was perfectly prepared to become the first full-time tournament director for the fledgling Bass Anglers Sportsman Society.

B.A.S.S. founder Ray Scott credits Sharp with ensuring that the cancer of cheating never got a foothold in the Bassmaster Tournament Trail. Sharp was a fair but uncompromising administrator of tournament rules, Scott noted, adding, “The anglers understood that there’s a right way, a wrong way, and Harold’s way.”

In his 18-year career with B.A.S.S., from 1969 through 1986, Sharp created a system of bass competitions and an easy-to-follow rulebook that were widely copied by tournament organizations that came along later. He helped build participation in the events, he advocated for increased payouts, he recruited sponsors, and he played a major role in the creation of signature B.A.S.S. events including the Bassmaster Classic, the Top 100 Pro-Ams, and the first big-money event, B.A.S.S. MegaBucks.

While he was perfectly suited to organizing and running tournaments, that wasn’t the first, or even the most important of his contributions to the evolution of modern bass fishing.

Sharp couldn’t get away from his job at Southern Railway in Chattanooga to fish Ray Scotts first All American at Beaver Lake, Arkansas, but he scraped up the $100 entry fee and enough comp time to fish the Dixie Invitational at Smith Lake, Alabama, in October 1967. He finished 18th and won the big-bass trophy, but more importantly, he met outdoor writer Bob Cobb and tournament angler Don Butler, who had recently formed the Tulsa Bass Club.

Sharp liked the idea so much he got a copy of their bylaws and set up an organizational meeting for the Chattanooga Bass Club upon his return home. With Scott in attendance, Sharp signed up 19 members and was elected president. That same day, January 12, 1968, Sharp became the second member of B.A.S.S., behind Don Butler. He and Scott met throughout the day, drafting rules and regulations for B.A.S.S. and for the Chattanooga club, which became the first in the nation to affiliate with B.A.S.S.

Sharp’s ideas resulted in what is now known as the B.A.S.S. Nation, a network of affiliated bass clubs in 47 states and 11 foreign nations.

Impressed with his new friend’s organizational skills, Scott recruited him to organize the Bassmaster Seminar Trail which used pro anglers including Roland Martin and John Powell to present how-to seminars to packed houses in 101 cities across the nation. At every stop, Sharp presented a short pitch about bass clubs and offered to meet with anyone interested in organizing one. After the seminar tour was over, Sharp examined a map showing the locations of all the affiliated bass clubs, and he saw clusters of clubs around every stop on the circuit.

Over more than a half-century, the B.A.S.S. Nation has played a vital role in crusades for clean water, healthy aquatic resources and wise fisheries management. In this, too, Sharp led the way. He and his Chattanooga Bass Club raised enough money to hire attorneys and join B.A.S.S. in suing more than 200 companies they accused of polluting public waters. Labeled “Peg-a-Polluter,” the initiative drew national attention to industrial pollution of waterways and helped provide the impetus behind the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and passage of the Clean Water Act.

He competed in Scott’s second bass tournament, held on Smith Lake, Alabama, and he became the second member of B.A.S.S. in 1968, after Don Butler. He organized the Chattanooga Bass Club, which became the first bass club to affiliate with B.A.S.S. He drafted rules and guidelines for the organization of clubs, many of which remain in effect for the B.A.S.S. Nation, which has affiliated clubs in 47 states and eight foreign nations.

Sharp retired from B.A.S.S. in 1986, shortly after Scott sold his company to his executive vice president, Helen Sevier, and a group of investors. He moved back to Chattanooga and launched his own company, “Fishin’ Talents,” which represented several professional anglers of the time. Sharp died in 2015, at age 88.

http://https://m.bassmaster.com/video/legends-lore-harold-sharp

Harold Sharp

George Cochran (1950—) When George Cochran began his fishing career as a child in Arkansas, he did it in a very quiet and unassuming fashion. His father wasn’t a fan of fishing

He maintained that demeanor which ultimately earned him the moniker of “Gentleman George” among his fishing peers as he blazed a trail to more than $2 million in bass tournament winnings.

Cochran’s passion for bass fishing blossomed when his family moved into the Lakewood subdivision of North Little Rock, where a neighbor began showing him the correct way to rig-up and fish different lures.

He became obsessed, so much that he struggled to keep up with his high school studies because of his time spent fishing and hunting. In fact, he missed so many days in high school during his senior year that any time the telephone rang at home, his mother always knew that it was the high school principal asking, “Where is he today? hunting or fishing?”

George went on to graduate high school in 1965 and earned a degree at Arkansas A&M College in 1971. He married the love of his life, Debbie before taking a job with a railroad company.

His bass fishing prowess and tournament skills grew throughout Arkansas where he won two state championships and gathered more than 50 different tournament titles.

It wasn’t until he began fishing the B.A.S.S. tournament trail that people really started to take notice. He placed 31st in the first Bassmaster tournament event he competed in, the 1979 Florida Invitational on the St. Johns River.

George went on to qualify for 21 Bassmaster Classics and capture seven Bassmaster tournament titles. He won the 1987 Bassmaster Classic on the Ohio River and the 1996 Classic on Lay Lake in Alabama. He competed in 244 Bassmaster events and earned money in 150 of them, logging 54 top 10 finishes. His winnings grew to more than $1.1 million before retiring from Bassmaster events.

He added another $1 million from FLW Tour events and is one of only five anglers to win both the Forrest Wood Cup and Bassmaster Classic. He appeared in nine Cup events and fished 118 FLW sanctioned tournaments. He won two and had seven top 10 finishes.

He built his career as a shallow water fishing expert and was one of the best to ever fish professionally. He continues to fish and duck hunt around his Arkansas home.

- 1987 Bassmaster Classic Champion

- 1996 Bassmaster Classic champion

- George Cochran at the 2005 Forrest L. Wood Championship at Lake Hamilton.

George Cochran

He was born and raised outside of Charleston, South Carolina, on his family’s farm. When he was fourteen, he left the farm and began working at his uncle’s marine dealership, where he garnered a love for boats and racing. Earl was so good at maneuvering a boat at high speeds, that he began racing boats at the tender age of sixteen. In 1973 he joined the Mercury Racing Team where he raced for eight years and captured nine National titles and two World Championships.

As the “bass boat boom” was exploding, in 1975, he accepted a job with Hydra-sports Boat Company, in nashville, to work on boat design, research and development. During this time, he became the first person to ever drive a bass boat with a V-6 outboard motor on it.

In 1983, he left Hydra-sports to begin his own boat company: Stratos Boats.

Under his leadership, Stratos quickly became a leader in the fiberglass fishing boat industry. In 1987, he sold his company to Outboard Marine Corporation and became President of the OMC fishing boat company, until 1996.

In 1996, with several of his key management team from OMC, he founded what has become the leading producer of wood-free boats in America: Triton Boats.

Over the past thirty years, Earl Bentz and his team have been credited with developing many of the designs and system standards on today’s bass boats. Among them: 6-gauge trolling motor wiring as standard equipment; automatic circuit breaker electronics; wood-free boat construction; retractable passenger grab handles and the most recent innovation: the retractable boarding ladder that received the “Award of Excellence” for lifesaving innovations by the National Safe Boating Council.

Along with his love of fishing, Earl has also found time to become one of the most respected hunters around. When hunting season arrives each September, his staff knows that you can probably find him in the woods somewhere, looking for another mount to add to his already impressive collection.

In case you think he has neglected his civic duties: he has served on numerous industry boards including: the National Marine Manufacturers’ Association; the American Sport Fishing Association; the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation; and on the board of the Middle Tennessee Boy Scouts, to name a few.

Between his personal and corporate donations, he has helped raise millions of dollars for some of America’s most worthwhile charitable organizations and his unwavering sponsorship of anglers across america is legendary.

As fellow Hall of Fame board member, and ten-time Bassmaster Classic qualifier, Guy Eaker told me recently: “in almost thirty years of working with Earl, I’ve never had a written sponsorship contract. One day, several years ago, I asked him if he thought we needed one, and he said “if you can’t trust me with my handshake, then we don’t need to work together.”

He and his wife, Janet, reside in Nashville, Tennessee, with their three daughters.